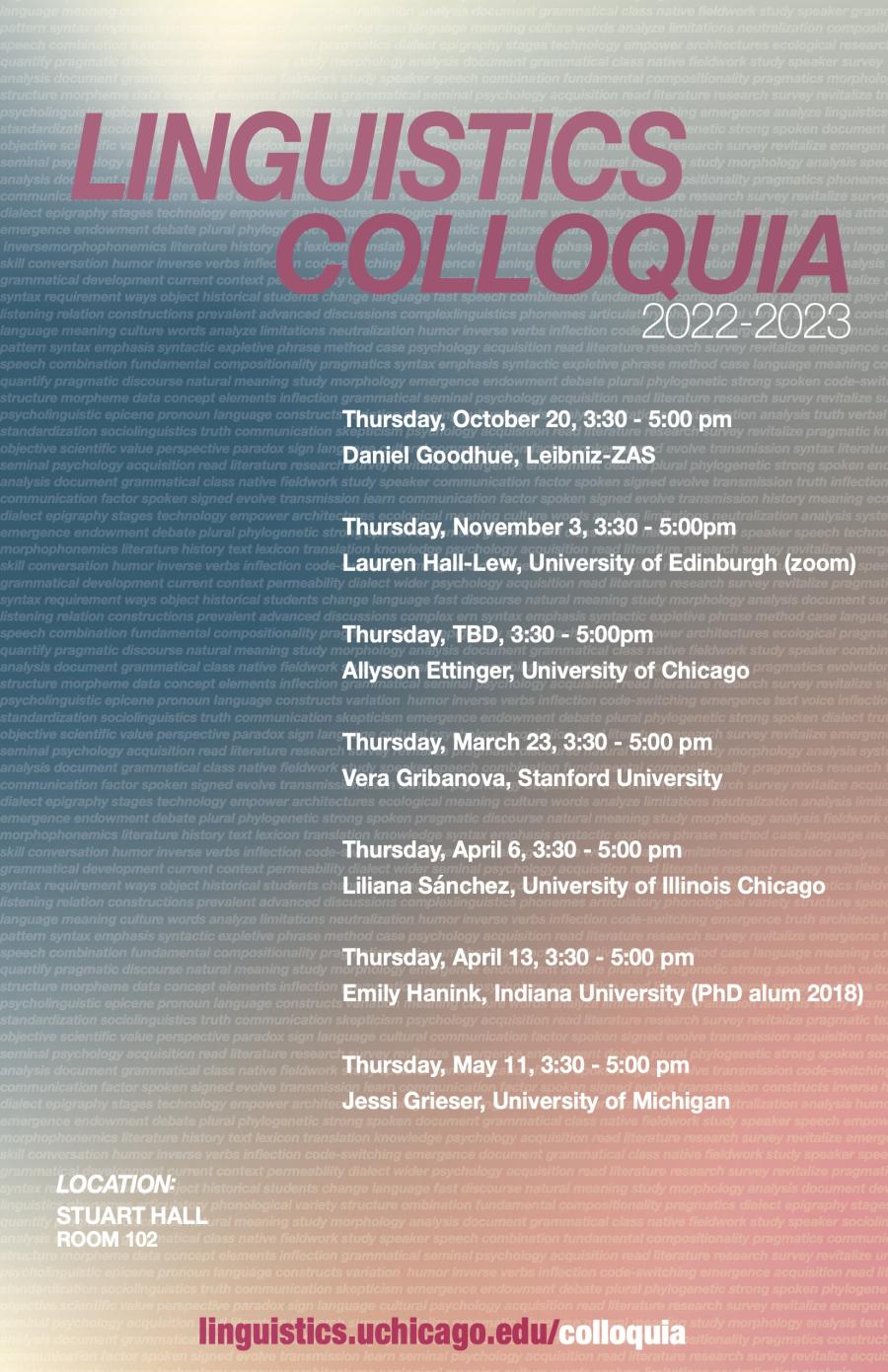

Thursday, April 6 , 3:30 - 5:00pm

Liliana Sánchez, University of Illinois Chicago

Stuart Hall, Room 102

Our second colloquium this quarter will be from Liliana Sánchez (University of Illinois Chicago), titled "Structuring discourse in Southern Quechua and Spanish: Discourse connectors, switch-reference, and evidential markers".

Structuring discourse in Southern Quechua and Spanish: Discourse connectors, switch-reference, and evidential markers

Evidentiality has been extensively studied across languages from the morphosyntactic perspective (Aikhenvald 2004), the semantic perspective (Faller 2004), and more recently from the discourse perspective (Fetzer & Oishi 2014). Fetzer and Oishi (2014) identify E1 languages that obligatorily mark evidentiality through grammaticalized means (evidential morphemes, tense, etc) and E2 languages that optionally mark evidentiality through lexical or non-verbal means. The relationship between evidential markers and discourse connectors in E1 languages has been less explored (Muysken 1995). Sánchez, Andrade and Gonzalo (In prep) focus on the distribution of Southern Peruvian Quechua (SQ) evidential/focus markers such as -mi (attested) or -si (unattested) and discourse connectors such as hina ‘like’ (Muysken 2015) and chaymanta ‘then’ and explore the role that evidential suffixes have on the way in which discourse units are structured. This interaction is exemplified in the following excerpt from a Southern Peruvian Quechua narrative:

[1] chaymanta warmacha caja-pi apa-mu-sqa rana-cha-ta.

Then boy-DIM box-LOC bring-DIR-PST.REP frog-DIM-ACC

“Then the boy brought the frog in the box”

[2] hina-spa chura-n wakin animal-cha-n-pa ladu-n-man

Then-SS put-3.S some animal-DIM-3.S-GEN side-3.S-ABLA

“Then (same subject) (he) put it next to some of his animals.”

[3] hina-pti-n chay sapu chiqniku-spa-m

Then-DS-3.S that toad smile-SS-FOC/EVID (fixed expression)

chaki-cha-n-ta foot-DIM-3.S-ACC

kachurpari-n.

let go-3.S

“Then the toad, smiling (at the frog), let its leg go”

[4] hina-pti-n-mi warmacha saputa qaqcha-n.

Then-DS-3.S-FOC/EVID boy toad-ACC tell off-3S

“Then, the boy told off the toad (attested)”

This discourse fragment from a picture-based elicited frog-story narrated by an adult Quechua-Spanish bilingual speaker shows a sequence in which the discourse connector chaymanta in [1] is unmarked, followed in [2] by hina marked with the same subject marker -spa. In [3], the subject changes and hina receives the different subject marker -pti and in [4] the subject changes back to the boy and hina is marked with -pti and the attested evidential/focus marker -mi. This last utterance breaks the sequence of events in which the boy introduces the frog to the animals and initiates a new sequence in which the boy chastises the toad. Sánchez, Andrade and Gonzalo (In prep.) analyze 18 frog stories produced by adult Quechua-Spanish bilingual speakers in order to understand a) the distribution of evidential marking of discourse connectors, and b) the extent to which such marking is required. The findings revealed that the pattern in [4] in Quechua holds mostly for speakers who used the attested form -mi, and the marking of evidentiality on discourse connectors depends on the perceived sequence of the events. We propose that by adding a same/different subject suffix to the discourse connector, the speaker is guiding the listener to pay attention to subject (topic) continuity in the sequences of events and by adding an evidentiality suffix the speaker is establishing their commitment to the grounds assigned to a first sequence of events or renewing its commitment to a previous one. In this talk, I will also present results from the Spanish data produced by the bilingual participants in which the reportative discourse connector dice, although with a more limited distribution than their Southern Quechua counterparts, establishes/ renews the speaker’s commitment to the grounds assigned to the sequence of events. First language, age of acquisition and patterns of language use effects on the distribution in both languages will also be discussed.